Mark Crosby ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

Monash University apporte des fonds en tant que membre fondateur de The Conversation AU.

Voir les partenaires de The Conversation France

This article is part two of The Conversation’s “Business Basics” series where we ask leading experts to discuss key concepts in business, economics and finance.

How governments should manage their budgets, and how interest rates should be set, are two of the most important questions in economics.

Ideally, both work hand in hand to ensure the best outcomes for the economy as a whole. But they are enacted by different branches of government, and fall into different buckets within economics.

Budgeting – the way governments tax and spend – falls within the domain of fiscal policy. In contrast, the management of credit and interest rates falls into the domain of monetary policy.

With the recent federal budget handed down amid an ongoing battle to tackle inflation, both topics have dominated recent news coverage, so it’s important to understand the difference.

Paying tax is an unavoidable fact of life, but is needed to support spending on government services such as hospitals, roads, schools and defence. Taxation and spending decisions are made on different scales at every level of government, and form the basis of a government’s fiscal policy.

of Western Sydney airport" width="" />

of Western Sydney airport" width="" />

Traditionally, fiscal policy was seen as a very simple equation.

Governments should spend only as much as they earn through taxation, and only take on a small amount of debt for things like longer-term infrastructure projects.

But when economic growth falls, tax revenues also fall, forcing governments to cut spending to balance their budgets. Such spending cuts come at precisely the wrong time and are only likely to further worsen economic growth.

Noticing this pattern, economist John Maynard Keynes was the first to question this traditional wisdom, arguing that fiscal policy should be “countercyclical”.

According to Keynes, when economic growth falls, government spending should increase, only falling back as the economic recovery plays out.

Under a Keynesian approach, it’s therefore wholly appropriate for governments to issue debt to fund spending increases as the economy weakens.

The problem with this view of fiscal policy is that some governments have arguably abused their licence to spend, relying on ever-increasing levels of debt.

Greece famously suffered a spectacular debt crisis after the global financial crisis in 2008, but other European countries such as France, Italy, Portugal and Spain also have high and problematic levels of debt.

Chronically high debt can lead to higher interest payments on this debt, which in turn can limit a government’s ability to spend to support its economy.

Monetary policy affects the economy via a different lever.

By changing the relative cost of borrowing money, changes in interest rates affect the aggregate level of spending in the economy.

This in turn can impact inflation – increases in the general level of prices.

Cuts in interest rates will tend to stimulate demand and push prices up, while rate increases reduce demand and push prices down.

Interest rates are typically set by a country’s central bank, whose primary role is to keep inflation low.

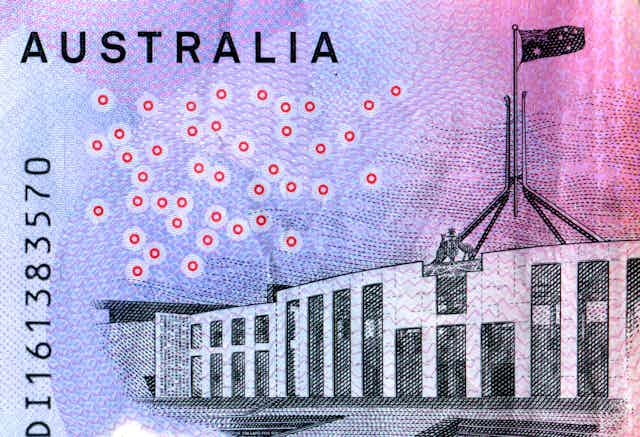

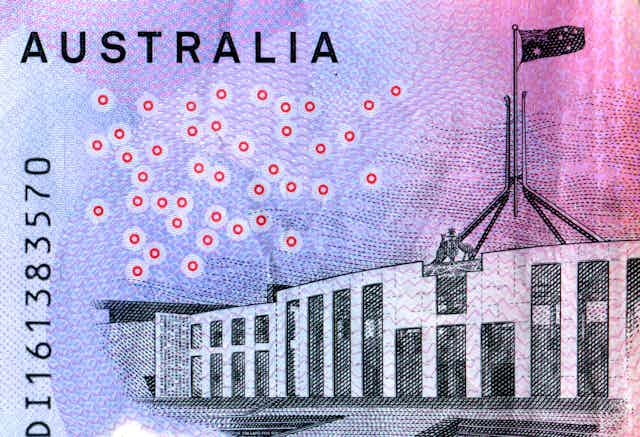

Our own central bank – the Reserve Bank of Australia, sets rates to meet an official inflation target of between 2% and 3%.

Alongside Keynes’ writing on fiscal policy, he and other economists argued that interest rates should be reduced as an economy heads into recession, to support borrowing and spending by businesses and consumers.

Coupled with higher government spending, keeping interest rates lower in a recession should theoretically speed up economic recovery.

The merits of a Keynesian approach were borne out clearly in Australia in both the 2008 global financial crisis and the COVID pandemic.

Most recently, the pandemic saw the Reserve Bank cut interest rates to almost zero. Simultaneously, the government supported the economy with a wide range of spending programs, including big boosts to welfare payments and a generous JobKeeper program to mothball Australia’s workforce.

As a result, unemployment quickly returned to low levels and economic growth recovered following the lifting of restrictions.

Emergence from the pandemic left us with a different problem. Inflation surged and remained stubbornly above the Reserve Bank’s target range, forcing the bank to repeatedly raise rates to try to tame it.

At the same time, the government has been trying to support Australians through a cost-of-living crisis.

Now, critics of the government have argued that further spending to support Australians could unintentionally put further pressure on inflation and force the Reserve Bank to keep interest rates higher for longer.

Such challenges reflect the fact that our understanding of best practice for fiscal and monetary policy is constantly evolving.

Problems with burgeoning state debt have prompted debate on the former, and whether there should be limits on governments’ ability to issue debt.

These could include limits to public debt, or new oversight authorities to monitor levels of public spending.

And on monetary policy, a recent review of the Reserve Bank considered requiring a “dual mandate” that would force it to give equal consideration to employment and to inflation goals, as is currently required of the US Federal Reserve.